The pursuit of knowledge and truth.

I often think of philosophy as something deeper than the mere evaluation of cogency in arguments, and logical constancy. Contemporarily, philosophy has taken a rather compartmentalized role, as something distinct from science, or art, or religion, just as everything else has. The branches of knowledge which can be accessed today are cut from their unity, being present as an isolated part, dead to the whole and the life that once sustained it. But in reality, a matter of simple observation will show that the branches of knowledge do not tend take on this isolated format, but are altogether instantiated such that this compartmentalization does not manage to wholly divorce things from one another.

Science only exists because it takes its roots in philosophy, and the many branches of science are interrelated, such, as one can note, when he looks at the mathematical patterns present in biological forms, the laws of physics which can be expressible in algebraic relations, or the laws of chemistry which point to or coincide with the laws of physics. So what is philosophy? The ancients did not seem to—insofar as I can see— have this concept of firmly instituted fields of study, separate from each other; the point we have reached to get here is indicative of our progress, but I also think that, for them, the absence of firmly delineated boundaries among disciplines also highlighted the one underlying pursuit in which all men of learning were engaged: that is, knowledge. In modernity, we have reached this development in the accumulation of knowledge, sophisticated distinctions, and experience only to lose sight of this underlying pursuit and its heights amidst the mass confusions of ambivalent motivations and passions that affront human beings. Most knowledge today has become some means in service of the wrong things, out of proper structure, out of hierarchy, and one could even say, possibly inverted. People do not learn in order to pursue knowledge as often anymore, the branches of knowledge available today have become mere pragmatic objects for ends the most diverse, e.g. as a profession occupying a cog-like role in today’s society and all the benefits which that entails, as a means for status, fame, or power and control.

Herein lies the importance of ethics, i.e. to properly search out the ultimate end to which your actions converge. If such a thing is not clearly delineated throughout an individual’s life, he is likely to fall prey to whatever dominant force, ideal, or motivations inhabit his social means, which is constituted—more immediately and basically—of passions, of interpersonal relations and channels of communication like the media, or the internet. More mediately—albeit also immediately depending on the person—through the enduring forms of communications handed down to us in history such as traditions, works of literature of all kinds, and institutions. Hence the importance of a healthy social fabric set in proper hierarchy, in which each thing inhabits its proper place. Such a thing will be transmitted from generation to generation as a guide to individual life. Notwithstanding, this is precisely what we are lacking as human beings, as persons oriented in truth; one must take full responsibility for his acts and decisions in life, clearly determining his values and all that goes against them in favor of greater integrity, allowing for his knowledge and his achievements to be properly transmitted to posterity.

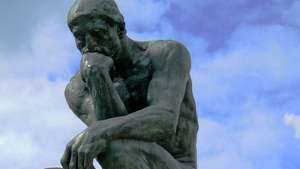

So what is the way of life which the philosopher promulgates? Some might say the pursuit of truth, others more generally, the pursuit of knowledge as that which presupposes truth, because regardless of a proposition’s truth or falsity in content, it remains a true state of affairs, that it is true, or false. Whatever knowledge one has, as long as truth is discernible from untruth it presupposes truth. Then, what is left for one to deny would be either truth or the possibility of knowledge. But, in either case, such positions are self contradictory unless one refrain from making any statements whatsoever. For one can question of the proposition that denies truth, whether that proposition is itself true; or, in the same manner, one could ask of the one who denies knowledge, how he himself came to know that.

It is interesting to observe how in reality the most abstract principles manifest themselves in the most concrete of ways: the principle of non-contradiction states that one thing cannot be two opposites in the same respect, a thing cannot be and not be concomitantly, someone can not run and walk or inhabit two different locations at the same time. Likewise with the impossibility and possibility of things, the main issue at hand being what we just derived with regards to truth and knowledge. There can be no person who is absolutely ignorant, or completely grounded in lies. Always, any particular person will have some measure of knowledge with which to base his life on. In what concerns this, something which is often said by the Brazilian philosopher Olavo de Carvalho comes to mind: Sincerity and intellectual honesty are of prime importance in the love of wisdom. That is, to not deny what you know, and not affirm what you do not know. Taking this as the basis upon which we stand, we can extend it to the pursuit of knowledge and the love of wisdom in that knowledge, as Pythagoras defined it. This wisdom, as something which is inextricably linked to one’s personal integrity and virtue presupposes a unity between his knowledge and his moral posture, a consonance and not a dissonance between what one knows and how one acts. Drawing on that same Brazilian philosopher, we can take a very useful definition of philosophy, as it being the search for the unity of knowledge in the unity of consciousness. Given this, knowledge takes on a transformative role as contrary to a utilitarian one, this time, less compartmentalized.

The way of life of the philosopher can be applied to learning as something which transforms his very life, something that shows his acquired understandings, insights and skills as not separate from each other, but as united, wholly applying to life. In this sense, one learns something not for the sake of some misplaced, disordered end, but to amplify one’s horizon of consciousness, to separate truth from falsehood, to contemplate the possibilities and impossibilities of reality, and to comprehend the unity that reality transmits in one’s own horizon of consciousness trying one’s best to emulate and synthesize it such that it is within the laws of truth; for what is real is not untrue. Thus what informs and underlies the learning of any discipline or subject in an individual’s life is the pursuit of knowledge and the attainment of all things true. Truth, a transcendental among the other two transcendentals (beauty and goodness) postulated by Plato, should, along with all things high be placed at the top end of a human being’s hierarchy of values, as the guiding principle of his action.