In what concerns the nature of existence, two distinct definitions seem to be relevant. One defines it as a property, as something to be had by other subjects, the other in the broadest possible way as anything that is, anything that can ever come into one’s field of consciousness, such that by the mere fact that something came into awareness it exists, the concern here is then to determine not what does and does not exist as there is nothing that does not exist, but what is the manner of an object’s existence. From this definition it follows that:

-Everything that has a manifest existence necessarily had a prior possibility of existence.

-Possibilities are not material, for they are not manifest

-Possibilities of existence are subsistent in reality, else things would not come into being.

-Therefore things necessarily have an independent existence of their manifest forms in some latent way or other.

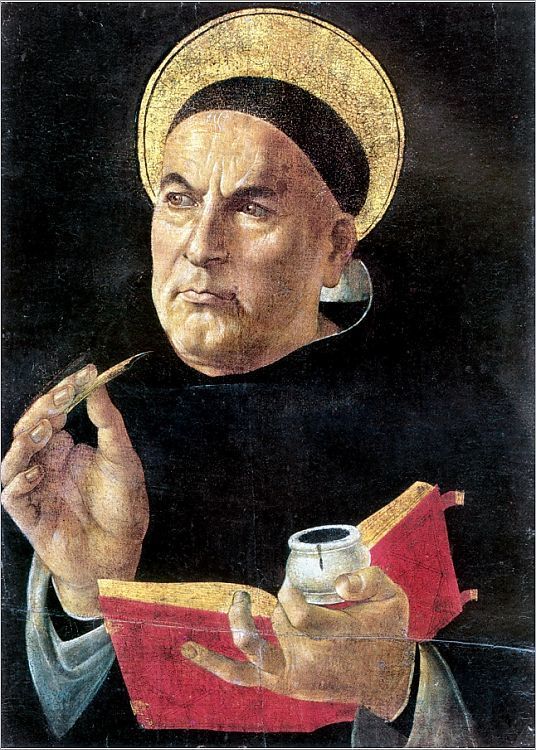

However, in reading St. Thomas Aquinas it is found that he defines existence in a more restricted sense, as a property and as distinct from the essence, which stands in stark contrast to the second definition mentioned above, which does not have the essence as separate from the existence of a thing, but as the very thing itself. This leads to either one of two suppositions, either there is no intersection on the object being referred to among the definitions and thus different terms must allocated, or, there is, and one must be more wrong than the other in their respective points of contradiction. The definition of Aquinas retains that God is the only one in whom essence is not distinct from existence and that, existence is given to other beings by Him, as He is the first cause and uncaused cause. If that were not the case each being would be the cause of itself. The argument is demonstrated thus: “First, whatever a thing has besides its essence must be caused either by the constituent principles of that essence (like a property that necessarily accompanies the species — -as the faculty of laughing is proper to a man — -and is caused by the constituent principles of the species), or by some exterior agent — -as heat is caused in water by fire. Therefore, if the existence of a thing differs from its essence, this existence must be caused either by some exterior agent or by its essential principles. Now it is impossible for a thing’s existence to be caused by its essential constituent principles, for nothing can be the sufficient cause of its own existence, if its existence is caused. Therefore that thing, whose existence differs from its essence, must have its existence caused by another. But this cannot be true of God; because we call God the first efficient cause. Therefore it is impossible that in God His existence should differ from His essence. Secondly, existence is that which makes every form or nature actual; for goodness and humanity are spoken of as actual, only because they are spoken of as existing. Therefore existence must be compared to essence, if the latter is a distinct reality, as actuality to potentiality. Therefore, since in God there is no potentiality, as shown above (Article [1]), it follows that in Him essence does not differ from existence. Therefore His essence is His existence. Thirdly, because, just as that which has fire, but is not itself fire, is on fire by participation; so that which has existence but is not existence, is a being by participation. But God is His own essence, as shown above (Article [3]) if, therefore, He is not His own existence He will be not essential, but participated being. He will not therefore be the first being — -which is absurd. Therefore God is His own existence, and not merely His own essence.” De <https://aquinas101.thomisticinstitute.org/st-ia-q-3#FPQ3OUTP1>

The argument above suggests that in the frame of actuality and potentiality, of form and matter, existence stands as an actuating principle. Something which is elaborated further in question 4, Art. I of the Summa: “Nevertheless because created things are then called perfect, when from potentiality they are brought into actuality, this word “perfect” signifies whatever is not wanting in actuality, whether this be by way of perfection or not. Reply to objection 2: The material principle which with us is found to be imperfect, cannot be absolutely primal; but must be preceded by something perfect. For seed, though it be the principle of animal life reproduced through seed, has previous to it, the animal or plant from which is came. Because, previous to that which is potential, must be that which is actual; since a potential being can only be reduced into act by some being already actual. Reply to objection 3: Existence is the most perfect of all things, for it is compared to all things as that by which they are made actual; for nothing has actuality except so far as it exists. Hence existence is that which actuates all things, even their forms. Therefore it is not compared to other things as the receiver is to the received; but rather as the received to the receiver. When therefore I speak of the existence of man, or horse, or anything else, existence is considered a formal principle, and as something received; and not as that which exists.” De <https://aquinas101.thomisticinstitute.org/st-ia-q-4#FPQ4OUTP1> .

Normally, when considering possibilities and actualities, one would think that potentiality precedes actuality by the proposition that, for something to exist it must necessarily have a prior possibility of existence. However, if we reason through a causal chain, we find that in order for something to exist there must be something actual there to be its efficient cause, for things cannot be brought about unless there is something actually there to bring it about, that is, an efficient cause. Something that is devoid of this remains as pure possibility and therefore has no act in it and cannot come into existence. Thus in reasoning through efficient causes we find that actuality precedes potentiality ontologically.

Given all of the above, we may now come back to whether the two definitions have different referents. The answer is: in some respects. Insofar as the first makes a statement about all that is, it could, perhaps, constitute another subject of inquiry, but as it extends into possibilities such that it imprints a causal principle within each possibility, making each one the sole cause of itself, it stands to be corrected, for act precedes potency and existence is an actuality as opposed to a potentiality, a formal principle.